Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park Artist-in-Residence (2019)

Land Acknowledgement:

Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park resides on the ʻāina (land) of over fourteen ahupua’a (land divisions). These areas reside within the moku (larger districts) of Puna and Ka’ū on the mokupuni (island) of Keawe. The Kānaka ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiians) have endured the colonization of this ʻāina and their culture for hundreds of years, including the overthrow of Queen Lili’uokalani’s Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893. It is important to note that the Kānaka ʻŌiwi are still living through this history today, continuing to fight for the preservation of Mauna Kea and other sacred grounds across the island. The artistic work I produced as an Artist-in-Residence at Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park was directly influenced by the exceptional natural beauty found on this ʻāina. This statement serves as a land acknowledgement of the Kānaka ʻŌiwi people and their continued relationship with the ʻāina, and I extend an immensely deep and heartfelt aloha to have been allowed the privilege to explore and connect with these lands.

Introduction

In August 2019, I travelled to the Big Island of Hawai’i as part of the Artist-in-Residence program at Hawai’i Volcanos National Park through the National Park Arts Foundation. My wife, sister, and father-in-law joined me in a luxurious 3 bed/3 bath house (bigger than my own house) situated in the community of Nāʻālehu, which sits as the southern-most point of the 50 United States. During my one month stay I explored the island through its people (the warm “aloha” welcome goes deeper than just a saying) and its food (you haven’t had poke or shaved ice until you’ve been to Hawai’i), but my primary mission was to explore its natural landscape both inside and outside the national park. There is a surprising variety of climate and geography packed into an island whose area is 10 times smaller than my home state of Michigan; rainforests in the east give way to deserts in the west, jagged lava rock at sea level rise up to meet two massive 13,000 foot mountain peaks, remnants of tropical storms (as my wife and I found our first night there) evolve into perfect sunsets over limitless views of the ocean.

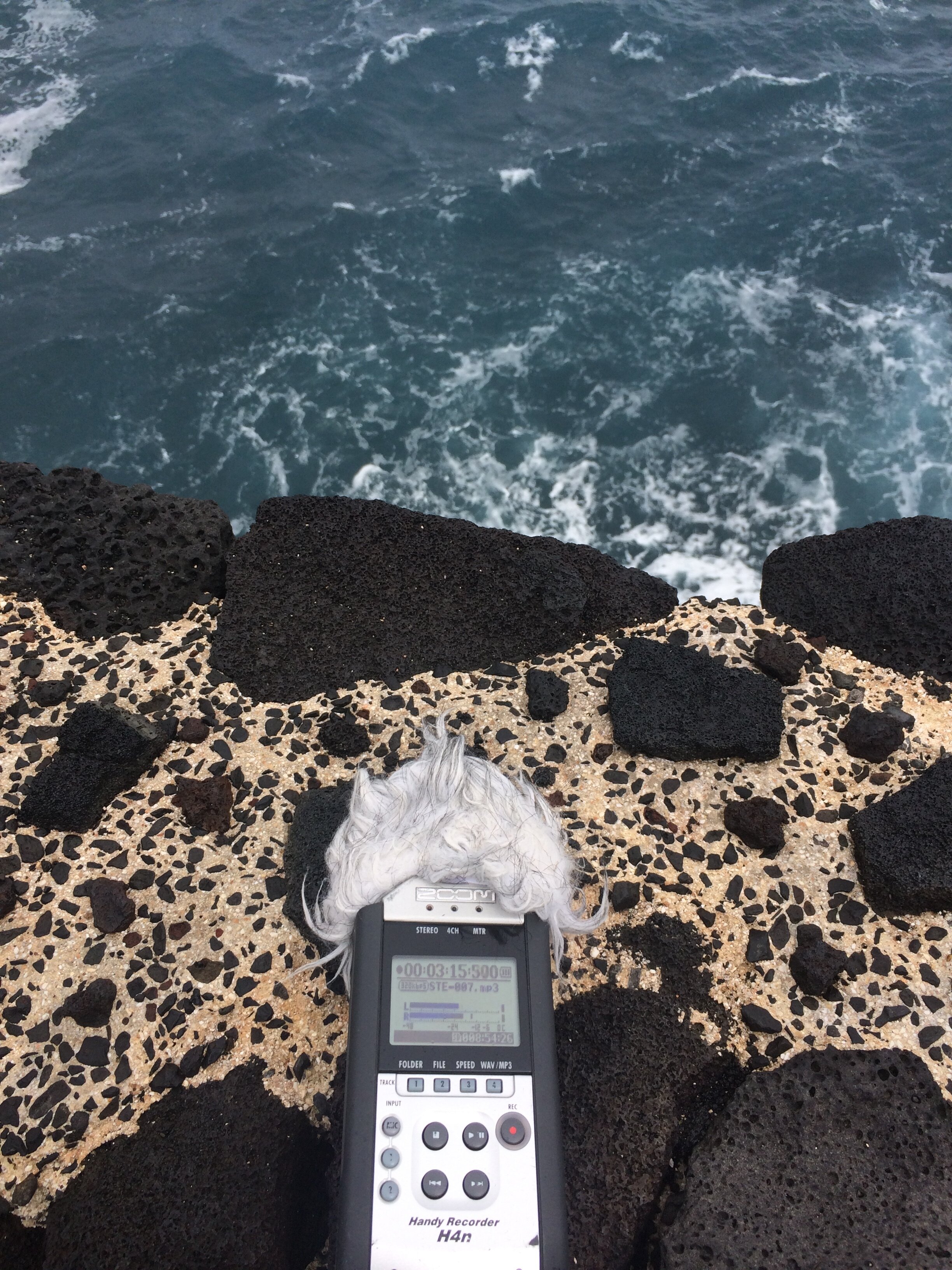

My goal as a musician/composer was to explore an aspect of the Big Island’s natural landscape that might be easy to treat as invisible: the soundscape. I ventured out everywhere from the trails to the tidal pools, deeply listening to the environment around me and capturing any sound that attracted my ear with a hand held Zoom H4 recording device. I began cataloging these sounds once I was back home (it is impossible to do any artistic work each day when the outdoor beauty of the island is calling) and let them gradually seep into my artistic work and unfurl into ideas for musical soundscapes. Now more than a year removed from the experience, it is clear that there is no one final product that represents my personal and artistic experience on the island. Below you will find a fractured collection of works that are both directly and indirectly influenced by my residency on the Big Island of Hawai’i. An immense thank you to Tanya Ortega and the National Park Arts Foundation for your support with this program!

Sample Recordings

To start, here are eight samples of natural sound I recorded while I was on the Big Island. Many of these make an appearance in the artistic works later on below.

Despite their uniform black appearance, Hawaiians have multifaceted words to describe lava rock. It can be smooth and ropey (pahoehoe) or pointed and jagged (‘a’a…pronounced “ah-ah” with the apostrophe being a glottal stop). This range of textures also gives each rock a unique sound when you strike them together; some have a hollow, resonant sound with a more definite pitch while others are more scratchy and crackly. I roamed through one of the many lava fields towards the end of the Chain of Craters road and spent some time recording a variety of lava rocks being struck together. Here is an edited clip of some of these sounds. Also, lava rocks are no joke. Even a minor slip can feel like falling on broken glass!

I wanted to push my sound recording techniques in a new direction for this trip, so before I left I purchased a hydrophone. This special microphone is encased in a layer of waterproof cable and resembles a black fishing line when dipped into the water. The learning curve for the hydrophone was steep for me, as the physics of water made the recording process much different than in the traditional air. Although there were many failed attempts, I did manage to get a few good recordings. The high pitched crackling you hear in the recording is ever present in the ocean. I have been told it is the sounds of fish munching on coral, but my research has pointed me towards this being the sound of snapping shrimp.

This was a lucky find! After many failed attempts recording in the ocean with the hydrophone, I shifted gears to recording in smaller tidal pools and happened to catch this hermit crab rolling a rock. I hovered the end of my hydrophone over him like some underwater U.F.O., capturing this sound as his rock scraped against the bottom of the tidal pool.

At the end of the Chain of Craters road is the iconic Sea Arch reaching out into the ocean. The visitor’s outlook has a wall that juts straight down from the face of the cliff into the ocean, and when the right wave came the effect against this wall was powerful. There are three separate recordings here, and the “pow!” in each of them has the perfect low-end frequency range for a sound that to me resembled a bass drum. I also love the sound of the excited kids in the recording!

My leg struck something as I was wandering out to look at the Pu’u Loa Petroglyphs. The shaking sound immediately made me stop. I had had a close call with a rattlesnake once in the South Dakota Badlands and I didn’t want to mess with whatever Hawaiian wildlife was at my feet. When I looked down, it was actually a plant with a little gourd on it. Relieved, I immediately spent some time recording it since it had a perfect hi-hat cymbal sound for my music later. Later on I excitedly shared this recording with a park ranger, only for him to flatly note that the species was invasive.

Whether you are deep into the Waipi’o Valley or walking out of a Target in Hilo, the sound of the coqui frogs are ever present on the Big Island. In this recording, you can first hear their distinctive two-note ascending call. Then, I give an example of the sound processing I apply to my recorded sounds. Using the computer software Max/MSP, I create a random chain of pitch-shifted delays to transform the sound of the coqui frogs into a harmonic swell.

While recording some time-lapse video footage at the Kahuku Unit (a recently acquired part of the national park that is a separate hour drive away from Hawai’i Volcanoes), I stumbled upon some crickets making sound in a nearby bush. The sounds of crickets are always fun to play with musically since they have a definite pitch and have a pulsing rhythmic quality. Like the coqui sound clip above, you will first hear my original field recording of the crickets (unprocessed) then a processed version created by feeding the sound through Max/MSP.

And of course, birds! (You will hear a lot more from me on this topic in a second). Although the soundscape in the main Hawaiian cities is dominated by invasive species (house sparrows, myna birds, zebra doves), I was fortunate to hear many of the endemic birds from Hawai’i like the ‘apapane and the nēnē. This recording is a compilation of the many bird sounds I recorded on the island. Some highlights include the aforementioned ‘apapane (the R2D2-sounding bird), the dawn chorus I recorded at 5 in the morning (!) at Kīpuka Kī, and the serenade I received from a parrot at the Buddha’s Cup Coffee farm.

Artistic products

Radiohead, “Weird Fishes”

As a stress relief project in Fall 2020, I gave myself the creative challenge of re-recording the Radiohead album In Rainbows using only my trumpet. No other instruments! This helped me develop a fresh relationship with an instrument I had played for over 20 years, using extended techniques and studio trickery to pull some wild new sounds out of the trumpet. In the process of recording this cover tune, the title “Weird Fishes” let me to add some of the underwater sounds I recorded with my hydrophone in Hawai’i (one of the few non-trumpet sounds I allowed myself to use for this project). As another test, I overlaid some visuals: the unused time-lapse footage of the Big Island’s ocean I had taken using my iPhone. It worked perfectly, and the result turned into the video below.

My time on the Big Island also influenced the way I approached my trumpet parts. I distinctly remember a moment in my residency where I sat at the edge of South Point Road in Nāʻālehu, marveling at the cycles of natural processes flowing around me: the rising/setting cycle of the sun, the constant churning of ocean waves, the millions of years of geologic forces that shaped the very island I was sitting on. The natural forces operating at different time scales inspired me to think about cycles, the idea of musical loops functioning in different realms of time. This is how I approached the two beginning trumpet parts: one is in a cycle of 3 beats while the other is in a cycle of 5. These uneven numbers cause the cycles to overlap and blur in interesting ways, and as the piece goes on more cycles are introduced (a third trumpet part enters on a displaced cycle of 5 sixteenth notes, while the bass line operates on a longer time scale over several measures and bar lines).

Lava Rock Beats

After sorting through all of those recordings of me smashing and clashing those lava rocks together on the Chain of Craters road, I cut out 19 short samples and fed them into a custom step sequencer (a visual beat generator) I made in the computer software Max/MSP. The sequencer was designed to churn out random patterns of beats, which I then finessed by adding, subtracting, or shifting beats over to my liking. This became the percussive foundation to these “lava rock beats,” where every sound you hear is a natural sound I recorded on the Big Island (the majority of which are from within the borders of Hawai’i Volcanoes National park). Some of the other sounds include birds (I believe it is an ʻōmaʻo), waves crashing at the Hōlei Sea Arch (makes a great bass drum hit), crickets in a grassy field, and this little shaker plant with gourds that my leg ran into on the petroglyphs trail.

The video you see here is a short excerpt from the beginning of the piece. You can hear the longer “director’s cut” of this piece below, which is a series of interconnected sections that last 1-2 minutes, each of the pieces flowing into the next as one long, dream-like sequence.

Octo Beat

Image Credit: Kanaloa Octopus Farm (https://www.kanaloaoctopus.com/)

I had the wonderful opportunity to visit the Kanaloa Octopus Farm, an organization dedicated to raising octopi in captivity in order to reduce the capture of octopi in the wild. They generously allowed me to stick my hydrophone in their tanks, warning me that it is unlikely an octopus makes much sound at all. Surprisingly, I was able to capture the sound of the octopus put its suckers on the hydrophone as well as spraying an underwater jet at it. I also captured sounds from water dripping into the tank from an external pipe. I took these sounds and electronically manipulated them into this short, one minute beat (you can also hear this piece incorporated as part of the “Lava Rock Beats”).

Bird research/podcast

Before my previous National Park residency (Great Smoky Mountains in 2018), I happened to be listening to NPR in my car as the author Jonathan Franzen came on to celebrate 2018 as the national “Year of the Bird” (the Migratory Bird Treaty Act turned 100 that year). My musical brain just about exploded when the radio program shared a recording of the lyrebird (if you haven’t heard this fantastical creature, stop what you are doing). The timing of this revelation just before my residency meant that I spent a lot of my time in the Smokies meditating on birds and bird song. The obsession continued into my Hawai’i Volcanoes residency, where I spent a significant amount of time doing additional online research each morning in the residency house before going out for the day’s hike. For my scheduled hour long “artist visitor’s talk” at the Kilauea Visitors Center, I made the risky decision to abandon my old format in favor of spending an hour flipping out about birds with my audience (a professional composer/musician I am, an ornithologist I am not), which seemed to go over well! This two year obsession came to a climactic moment in what I think is my most prized expression of my love of bird song: a podcast for my elementary music students. When COVID-19 shut down schools in the Spring of 2020, I adapted my elementary music curriculum to a virtual podcast format where my students could listen and participate in musical activities (sans screens). Even though this podcast is listenable for kindergartners, I designed it for all ages to be enamored by the mythical relationship between bird song and music. Enjoy!

Steam Shoe Video Clip

I knew the answer to the question before I asked it. On my first day in Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, I approached a park ranger and asked him where I might record some sounds of the volcano. He gave me a look. “It’s not making any sound right now…”

Kilauea is the most active volcano in the world, and 2018 was one of its most active years on record. By the time I arrived in 2019 I could only see the aftermath. The Kilauea Caldera had plummeted in depth from 280 feet to 1600 feet. 30-foot high hardened lava flows covered main roads in neighborhoods southwest of the park. So there I was: an artist-in-residence, whose primary mission was to capture natural sound to turn into music, standing on the edge of a silent volcano (What was I doing here?! Did they deserve to pick me?!). That is when I changed my approach and realized there was, in fact, sound all around me: Human sounds. Tourists. The soundscape here in the park was dominated by people (for better or worse). So then I began to think: What would human-volcano sounds be like? I recorded myself scuffling my feet against the pathway on the crater overlook. Later, I took these recordings and time stretched them to be 10x slower their original speed using a computer program called Paul’s Sound Stretch (this software was famous back in the day for time stretching Justin Bieber songs into epic soundtracks). Pairing this sound with a time-lapse recording of the steam emanating from the volcano, I got the result below.

Time-Lapse: Hybrid Nature video and Generative Waves video

Whenever I had a moment to pause at an overlook, I would setup my iPhone to grab 10 minutes of rudimentary time-lapse footage. I had no intention for how I would use these clips (or even if I would use them), but having the chance to work through these two video experiments might serve as stepping stones for my work in the future. The first work creates a “hybrid” environment of spliced recorded sounds from the island (wind, zebra doves, crickets, thunderstorm, coqui frogs) that were processed through Max/MSP and paired with an edited (but unprocessed) flow of time-lapse footage. The second video is a generative system in Max/MSP that processes the video footage using Jitter (a mirroring video effect, as well as a series of visual sound waves chasing each other) and creates music using a random note generator (no natural sound, only an FM synth with randomized adsr envelopes). These two works are more like installation pieces, where the videos you see here are only slices of the generative works that (theoretically) change infinitely over time.

Other Appearances

The creative/artistic process is never a straight line, and these projects from over the last year unexpectedly led me towards using smaller components of my residency experience in their creation. Although the field recordings I took on the Big Island of Hawai’i might not seem like a central feature of the works below, they are certainly an integral part that transformed each of these works into something special.

Currents: Mvt. 1

Currents is a massive, six-movement musical composition with elements of live chamber music, recorded music, and interactive electronics. It uses the process of sonification (turning data into sound) to transform weather/climate data into a visceral, musical narrative about our changing planet. The one minute clip above provides an abbreviated version of the first movement of Currents, which covers forty years of U.S. weather disasters in eight minutes. The three sets of natural sounds (crickets, ocean, birds) represent three different environments (land, sea, sky), functioning as an abstract barometer that allows us to check in and take readings on the health of three distant biomes on our planet. An underwater hydrophone recording from the Big Island of Hawai’i is used to represent the ocean. You can hear this as the crackling sound in the right speaker to depict the monetary cost of each individual weather event (the middle graph in green) and it also plays a significant role in the ending soundscape. Click here to look more at Currents.

Joey’s Dance Video

The Wayne State University music composition studio teams up each year to collaborate with the WSU dance studio, and in 2020 I had the opportunity to work with dancer/choreographer Joey Mattar. Joey’s vision of the piece was to have me create a chaotic collection of noisy sounds for him to dance to. Several sounds are used throughout the piece (zippers, sliding doors, chains and welders from my dad’s garage), but if you listen closely towards the middle of the piece you can hear the clank and scrape of Hawaiian lava rocks making an appearance.

l a n d s c a p e s

“l a n d s c a p e s” has been a two year side project of mine that seeks to depict natural environments through short, improvised music compositions. The “Ocean” collection featured me collaborating with my brother-in-law Terry’s guitar effect pedal wizardry. Although the recording was finished before my Hawai’i residency, I revisited it after my trip and added the hydrophone sounds you can hear in the first recording below. The second recording below comes from the “City Rainforest” collection I collaborated on with Michael Malis, a wicked pianist and one of the foremost leaders in the Detroit jazz music scene. The track blends together a wide collection of bird sounds, some of which came from my 5 am dawn chorus recording at Kīpuka Kī in Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park (the birds that sweep across the L/R speakers at 0:20 is one example). Click here to look more at the “l a n d s c a p e s” project